KEY:

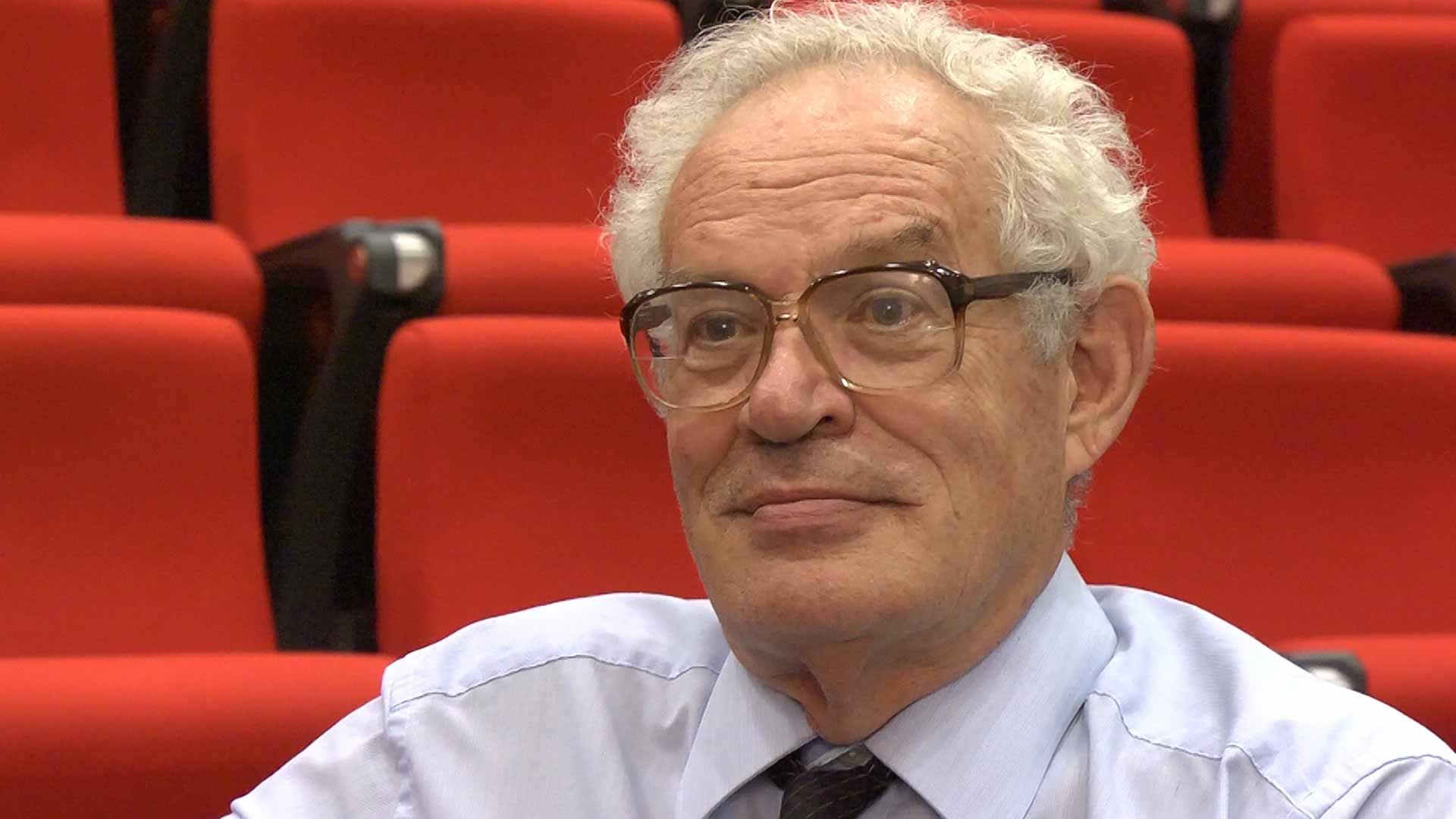

I: Interviewer Dr. Ivano CardinaleCG: Respondent Professor Charles Goodhart

I: We are with Charles Goodhart, emeritus professor in the Financial Markets Group at the London School of Economics and former member of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee. Professor Goodhart, thank you for agreeing to participate in this interview series on traditions of economic thought and their bearing on research and teaching in economics, which is organised by the Independent Social Research Foundation and Economics at Goldsmiths. We will start with the observation that, reading your work, it’s quite striking how you often compare different traditions or theories in economic thought as a way to identify and discuss key issues in monetary theory and policy. What are the main traditions or theories that you have found relevant in your work?

CG: Well, there’s obviously the Keynesian approach. Then there’s the quantity theory approach, and more recently one of my concerns is that the monetary aspect of theories has actually been written out of the DSGE models more or less entirely, because the transmission mechanism in those models goes directly from interest rates to the real economy without going through the transmission mechanism of monetary variables at all. So you have differences in views towards interest rate determination, the liquidity theories of Keynes, you’ve got the loanable funds theories of Dennis Robertson and then the classicists. You’ve got the quantity theory approach that goes back to Hume and Ricardo. So those I think I would describe as the main ones.

I: Before we go more deeply into the differences and the similarities between some of these theories, would you like to give an example, for example as to how they conceptualise the workings of monetary policy?

CG: Well, take the liquidity preference against the loanable funds approach. Keynes saw the interest rate as determined by, effectively, the demand and supply of money. In the short-run, I’m sure that he’s correct, but if you take a longer run period, if the central bank tries to set interest rates that result in a real rate of interest that differs from that that brings about a degree of equilibrium in the economy, then the economy either starts to move into ever increasing inflation along a vertical Phillips curve or alternatively slides into deflation. So that, if the central bank tries to bring about a nominal and real interest rate that is too far from that which equates ex-ante savings and ex-ante investment, then it causes such disturbances within the economy that the central bank is forced back into line.

In other words, in the short run I think that the Keynesian liquidity preference approach is the better one, but if you take the medium to longer term, then it’s actually the loanable funds, ex-ante savings and ex-ante investment that determines the real rate in the longer term. So it’s a question of what is the period for which you were thinking and that of course brings us back to one of the great problems of economic theory, which is, what is the time period on which you are focussing? Keynes and Robertson, for example, would have differed in terms of the specific time period that they were thinking about, with the Robertsonian day, and short period and long period. So dealing with time is always one of the great problems of economic analysis.

I: I imagine that when these theories inform policy—we will discuss to what extent they do— the distinction between time horizons is not clear-cut in the parameters of policy making; is that right?

CG: No, of course it’s not. You can get a very, I think, good example at the moment, because there is deflationary pressure within the economy. At the moment, for a variety of reasons we will not go into, monetary policy has pretty much shot its bolt. That means in the short run, at any rate, a more expansionary fiscal policy would seem to be highly desirable, but on the other hand the longer-term outlook for fiscal policy, with a rise in the ratio of old dependents to workers, means that fiscal policy is going to be under very considerable pressure over the longer term, say 10 or 20 years. So again there is a question of how far you concentrate on the immediate short run conjunctural issues, compared with how much weight you put on the longer term trend developments.

I: I’m sure there is no single answer about how it is done or why it is done in a way or another.

CG: No. Very rarely is there any single, clear answer in economics, which is actually why I found it so enjoyable to do economics, because at school we were always taught that there was one right answer. Even in subjects such as history, there was the correct answer and then everything else was incorrect. When one came up to university to do economics, one soon discovered that actually there wasn't a single answer, and I found that was enormously relieving and it was like being freed from shackles, so that one could think for oneself rather than try and memorise what one was told was the correct answer.

I: The intellectual enjoyment of this freedom is fully understandable. But in the part of your work involved with concrete policy decisions, this freedom came with a sense of uncertainty, I would imagine.

CG: Yes. There are always uncertainties. I was actually the author of a particular method of constraining the banking system, known as the corset, which was introduced at a time of great difficulty in 1974/75 and was used several times until 1981. This was a very conscious mechanism for trying to ensure that the banks rationed credit at a time when there was a great deal of inflation. While there were a number of pressures that made this—in my view—sort of the right answer at the time, nevertheless any rationing programme tends to distort... You never know what the underlying situation is behind it when you take it off, and, when we did take it off in 1981, the money supply exploded to a degree that we hadn’t been able to forecast, and Mrs. Thatcher got very angry with the Bank of England for allowing that to happen.

I: So you thought that was the right answer at that moment.

CG: Yes, and people do. David Cameron thought it was the right answer to hold a referendum on staying in the EU, and one’s not always correct in one’s eye.

I: It’s obviously easier to say this ex post, but in the moment of the decision, when there are many models or views in the room or in the decision space, how does the confrontation between models take place? Is it based on appealing to different theories, or to episodes in history, or to common sense as it can be defined at that moment? Is there a way in which these different points of view usually confront each other, or is this completely contingent?

CG: One uses models and ideas and structures of thought to try and make sense of the world around one. So one is always using a model of a kind, and one knows that that model is not entirely correct. One uses what models one has, to try and reach a judgment on what is the best approach, taking into account, as far as one can, the foreseen risks. The real problem, of course, is that one can’t foresee the future, and what really goes wrong is what one doesn't see coming. One of the reasons I’ve always bought insurance is that if you can actually estimate the risks and ensure against them, then they’re much less likely to happen. The problem is it’s the things that you don't know and it’s the unknown unknowns that get you.

I: I remember that, when I started reading Keynes, I was impressed by something in his writing style that sounded as if he were trying to convince other people: he was reasoning by argument, in a rhetorical way, and expecting counter-arguments. I often found that this was an interesting way to compare and take into account different views.

CG: Yes. There’s always a danger that, when you try and set out the argument that you don't like, that you make it into a straw man, that you don't actually see, or you don't present, the best arguments that the opposing view has. There are a lot of people who said that about Keynes. Dennis Robertson, in particular, was very upset because he thought that Keynes did not deal fairly with what Dennis described as the classical argument. That’s I think very common, that when you’re trying to present an analytical approach, you tend to put forward the alternatives in a way that doesn't really do them justice.

I: In principle, it might be possible to set out the opponents’ views in a way that could help explore alternatives, as opposed to simply confute the opponents’ arguments. Do you think that ever happens?

CG: Not enough. One of the disadvantages of economics is that people tend to adopt, even econometric, results that are consistent with their own priors. Too often, if I know the name of a particular economist and what he has done in the past and what his views are, and I see the subject he has written on, I will know what conclusions he’s going to come to before I even read the article. I do think that it’s unfortunate that econometrics and analysis are sufficiently malleable and flexible that you can always reach your preferred endpoint from whichever starting position you begin at.

I: In your way of reflecting on issues of monetary theory and policy, you often seem to adopt a broad methodological approach, in the sense that you often rely on history and the study of the institutional settings that are specific to the context. What is the role of these elements?

CG: I started as a historian. When I specialised at school, I specialised in history. Again, I think that economics is a splendid subject. Not only because there isn’t one correct answer to most of the questions that we get asked, but also because I think it’s a very good mixture of history, of knowing what has happened in the past and how we got where we are at the moment and much more rigorous mathematical analysis. I think that the combination of history and mathematics is a very good, very valid one, and in a sense puts us apart from some of the other social sciences. Now, having said that, I think that the subject from time to time varies too much in one direction. I have been doing monetary analysis with particular reference to central banking and for a time in the 1960s I was at LSE with Richard Sayers. I think that the Sayers School that he established at LSE, was much too historical, with too little attempt to frame it within the analysis, within a mathematical rigorous framework. But equivalently I think that in recent years it’s been very upsetting for me that history has been downgraded, and indeed that economic history is no longer required as part of the undergraduate economics syllabus, but also that the whole thrust of the subject has gone far too mathematical, with far too little reference and under-appreciation of historical evolution.

I: How do you envision the relationship between history and economics when it comes to formalization? One could think of at least two approaches. One is that a subtler understanding of history can provide better stylised facts, which could then feed into a model. The other approach may be closer to the idea of not aiming for an overarching mathematical model, but for a framework that includes mathematical models as well as other ways of understanding reality.

CG: Well, again, as a monetary economist I’ve been doing a lot on regulation and supervision, and one of the things that, in a sense, most upsets me about a lot of current economic theorising and analysis is that it assumes that the legal and institutional structure is given, and static. So that the only thing that happens is you get various shocks to the economy, and it all remains the same. Particularly if you look at what has been happening since the great financial crisis in 2008, that’s not the way it works. The way it works is you get a shock, that has certain effects, obviously some of which in many cases are adverse, and one of the results of that is you get a change in the institutional structure, for example in the financial regulatory system, that in turn feeds back into the way that agents behave. So you get an unorderly development; which again at various times you will face a new shock coming.

So you get a sort of continuous, evolutionary change, and what we don't have at the moment in economics is an evolutionary equilibrium in which the institutional and regulatory structure is changing along with the economy and with the severity of economic shocks.

I: It’s very intellectually demanding on the economist to develop such an approach, but I do agree that it is...

CG: Yes, indeed, it is. If you were operating with a model which does not include any evolution in the underlying institutional and legal structure, then you have to appreciate that your model is in many respects quite strictly limited, and you shouldn't be producing too much in the way of firm and confident policy proposals on the basis of a very limited and insufficient model.

I: In your writings, for example on the banking school and currency school, you highlight that the banking school has a preference for discretion over strict rules. Do you think that, to some extent, this depends on the views that these schools hold regarding the nature of the economic (and monetary) system?

CG: Yes, and the thing is that if you take a particular point of time, and you assume that everything in the way of the underlying structure of the economy is going to be constant, then it is almost always possible to set out a set of rules which will be optimal. Partly because of the time inconsistency problem, within a given structure, they will do better than discretion, but if you assume that the underlying structure is going to change, and change in ways that you simply can’t appreciate, then almost any rule that you initially set out will turn out to be mistaken, fallible, far less than optimal, because you don't know what’s going to happen. You don't know how the structure is going to change. You don't know how agents are going to behave. The world changes, and if the world changes you need sufficient flexibility to change the way that you operate within that.

I: Someone might object that this view assumes that the policy-maker has sufficient understanding of the changing dynamics of the system, and operates for the benefit of the system as a whole. What would you respond to this?

CG: I’d say you can’t. No one has that degree of insight about the future. The future is unpredictable, and we just don't know. This is Keynesian uncertainty. I think one of the key issues between those who describe themselves as post-Keynesians and those who describe themselves as neo-classical, neo-Keynesians, whatever, is that the latter group seem to believe that you know enough about the probability distribution to be able to come to some reasonably accurate judgment. Well, the post-Keynesians argue that there is so much uncertainty around that you actually can’t do that, that most decisions involve a leap of faith, which they do, because we can’t predict, and again that’s another feature that I feel very strongly about with respect to the use of economists in the modern world, which is that overall economists are primarily used for forecasting. That’s what we actually cannot do. We can’t do it. Our forecasts are horribly fallible.

I think that it would be much better if we were used to express what are the risks, what are the potential dangers that we see, rather than try to do a forecasting, which we really don't have the capability of doing. Yes, we can forecast six months ahead to a degree because there’s a great deal of momentum within the economy—if you don't have something like Brexit bringing about a sudden major change. Normally there’s a great deal of momentum, but by the time you’re coming two years down the road you really don't know very much. Here I would very strongly recommend Mervyn King’s recent book with the emphasis on uncertainty rather than the risk embodied in a probability distribution.

1

I: On the other hand, if there is such strong uncertainty, one could say that discretion is bound to be flawed.

CG: Everything is going to be flawed. If you don't know what the world is going to fling at you, and if you don't, you are not going to be able to make a decision which ex post is going to turn out to be optimal. I think that the emphasis on optimisation, which we have in much of the modelling that we have at the moment, is mistaken. We can’t optimise. We don't know enough about what the future is going to hold. What we really need to do is try and have an outcome which in most states of the world, as we can dimly perceive them, will not be too bad. Satisficing has always struck me as actually what we ought to be doing rather than optimising, because you can only optimise with any degree of success in a world in which you have sufficient information to do that, and we don't.

I: Let us go back to some of the distinctions and traditions of thought that are of particular interest to your work. You emphasize the distinction between the banking and currency schools. You also distinguish between two approaches to the very concept of money, and between theories that postulate that central banks set the monetary base or the interest rate. Are these distinctions orthogonal to each other, or are there deeper assumptions running through them?

CG: To a degree, yes. I think that the currency school have tended to be monetarists who tend to think that the central bank sets some monetary base. What was your third distinction?

I: Concepts of money.

CG: They tend to follow the Wagnerian approach rather than the approach that money derives out of considerations of power and trust and social inter-relationships, and also they tend to believe that money developed from a commodity rather than from a credit relationship between individuals.

I: You’ve mentioned that in some of these approaches there doesn't seem to be much space for a political authority.

CG: Well, I think that there is very much so, if you believe in the Chartalist approach, because essentially what one is saying there is that money derives from a credit relationship where one believes that the IOUs of – if you like – the most powerful elements in the state are the ones that are going to have the greatest continuing value in your transactions. It doesn't necessarily have to be the state. Initially some of the early work on the foundation of money had money as being the obligations of the priestly casts, for example, so you get a lot of money which was issued by temples as well as by governments. Yes, it’s an inter-relationship of power, authority, and therefore the likelihood that those obligations will be honoured. If you like, this kind of credit approach is one that virtually all, for example, numismatists and anthropologists have always adopted. It’s the commodity money, base money, currency school that has always been very much an economics only, without much relationship with the rest of the social sciences.

I: And yet, some strands of economic thought suggest that money emerged from pure market transactions...

CG: It didn't. It related very much more to power relationships. The Egyptians were one of the last pre-money societies, and what happened then was, when you were a pharaoh or whatever, and people were allowed to give you either their time, since they worked in your army or worked as your servants, or give you corn or grain or whatever it was, and this was an inefficient way of getting services from the general public. It was much easier to transform it into a monetary relationship so that you could buy whatever you wanted, and you would tax people in order to get hold of the resources and use money to get whatever resources you wanted. Money is really, in many respects, a social mechanism.

I: You even remark in your writings that sometimes taxation in currency was introduced exactly in order to pursue broadly political aims, such as forcing subsistence economies into monetary interdependencies with broader political entities.

CG: Indeed.

I: This is extremely interesting. Do you think that your reflections so far have a bearing on how economics is taught?

CG: Well, as I said earlier, I think that there should be much more history. If there had been greater reliance on history, I think there would have been a greater appreciation that a combination of a housing boom and credit expansion was highly dangerous. What happened, to a degree, was that in the US there were wonderful data on housing – all aspects of the housing market – which went back to the early 1950s. For 50 years you had monthly data on housing prices and all that. During these 50 years, if you held a diversified portfolio of houses across all the States in the US, there was only I think one or two quarters where housing prices overall on average fell. There were crises in New England at one stage and then the oil-producing states at another, but if you diversified you seemed to be safe.

If you took these 50 years, and ignored history elsewhere, and you ran your econometric analysis and assumed that the future was going to be like the past of those 50 years, it actually came about that you reckoned that a decline in housing prices over the whole of the United States of more than about four or five percent was an almost unimaginable event. It was basically on that premise that people went into, for example, all the sub-prime stuff, because it didn't matter if you were lending to poor people or people who are likely to get ill, who were on the fringes of the labour market and so on, because if they couldn’t repay you, for one reason or another, if housing prices didn't go down you could foreclose and you would still be safe, because you wouldn't lose any money, whereas you could sell.

The whole of the sub-prime exercise and the rest of it, which initially was done for the best of intentions, and it was to try and get the disadvantaged of America into the housing market. If you could rely on ever rising housing prices, it would have worked, but you couldn’t and history would have shown you that. So certainly I would want to start by reinstating history to a far greater extent into the syllabus; history not only of one country, because again any country has a sort of particularity. You want to have a history of two or three countries. Apart from that, I would hope there would be very much more humility, and to some extent also an appreciation that many of the mathematical models which are constructed, and many of them are constructed with a sophistication and a technical brilliance which is in many ways remarkable and very good, but they depend on their assumptions.

The assumptions of these models are frequently so extreme, and that particularly relates to what are known as the micro-founded DSGE models. To take one example, prior to the 2008 great financial crisis, the assumption in these models was that you could assume that everyone was the same, a representative agent, because no one ever defaulted. But if no one ever defaulted, either for strategic reasons or accidentally, then you never needed a bank because everyone could borrow or lend at a riskless rate. You didn't need money because, if nobody ever defaults, then your individual IOU is entirely acceptable for any purchase of anything anywhere. So you don't need money. So the whole basis of a construction of a financial monetary system depends ultimately on default. As my friend Dimitrios Tsomocos mentioned, you need default in order to construct a financial system, just as you need the devil and sin in order to construct a religious system.

It doesn't work when things can go desperately wrong. In both cases, and both for religion and for economics and finance. By having excluded what can go wrong within the financial system, they didn't have, as a result, a financial system. To some large extent they still don't. That’s what I mean by saying that the so-called microfoundations are not proper foundations at all. They simply don't reflect the reality of life. But trying to do so, trying to get a model that reflects all the complications of life, is such... particularly when we get the evolution that I was talking about in the underlying legal and institutional structure…. is so complex that we’re really a very, very long way from doing it. As long as we’re such a long way from constructing a model that approximates to reality at all, we have to be much more humble about what we can learn from these models.

And actually trying to forecast... and even after the great financial crisis, one of the problems has been that the models, because of the way they’re constructed, have always said, ‘We’re going to get back to equilibrium pretty soon,’ and we haven’t. The auto-correlation or consistency of errors resulting from the use of fallacious models has been remarkable.

I: If I understand you correctly, you are suggesting that it’s not just the knowledge of historical facts that is important, but also the need to use the historical method in the way economists reason, for example by comparing situations and realising that the future will never be like the past, although the existing stock of knowledge is reliable at least to some extent.

CG: Yes, absolutely. To give another example, I think one of the worst aspects of the Remain campaign in the recent referendum was when there was this production of the Treasury forecast giving a point forecast for what would happen to the UK economy in six years, and giving that in a specific sort of number, when you knew that you can’t do that kind of forecast. People I think recognised that that kind of forecast was just totally improperly precise and would never be that. We can’t forecast to that degree and to pretend that we can; I think it is counter-productive.

I: Because the changes in institutional structure and economic inter-dependencies are uncertain.

CG: Indeed. To take one particular topical example, we’ve had the decision to leave the EU and Brexit. That brings about a huge degree of uncertainty. We don't know what the effect of that uncertainty is going to be over the next quarter, let alone in 2017. There’s a very wide range of potential outcomes, even for this quarter. One of the complaints that I have about the use of economists is the way that they’re used to try and provide forecasts which are really not possible. To give a kind of analogy, it’s as if you were trying to do a weather forecast where your own forecast will influence the weather. Forecasting the weather’s difficult enough beyond about five days away, but the forecast that we make of the weather doesn't influence the weather itself. In economics, the forecasts that we make influence how people behave and how they respond. That just makes it another degree of difficulty. If meteorology is difficult enough in forecasting, economics is just a sort of quantum level more difficult.

I think it was Einstein, but it certainly was one of the very famous physicists, who said that he didn't want to be an economist because it was all too difficult. I think that’s right. It’s just a great deal more difficult in a very central, fundamental conceptual sense. The natural sciences, because the natural sciences don't respond... there’s some sort of problem about quantum theory which I won’t go into, and anyhow I don't understand. As a generality, nature doesn't respond to our experiments on it. In economics it does respond to our experiments on it. Therefore that interaction just makes it so much more complicated.

I: These issues are of the utmost importance, but they are also something that is difficult to achieve in educational terms: training economists who are rigorous in their thinking, but also able to relate that thinking to an extremely complex context. How do you think that we can move in that direction? Do you think that better interaction with the other social sciences can help economists?

CG: Yes. Undoubtedly. I think that behavioural economics, which tries to incorporate not only psychology but neuroscience, has improved our understanding of the way that people work, the way that they reach decisions, and with any luck will become incorporated into the structure of our models, but there’s a long way to go.

I: You mentioned earlier, when talking about monetary history, that the work of anthropologists and economic historians can be extremely relevant to gain an understanding of the economy. Now, do you think that there could be some gain to be made if economics students were also taught a broader set of empirical techniques? The techniques taught in economics mostly revolve around statistics, or sometimes simulations, but in the social sciences there is a much wider range. This could include, for example, the use of ethnography to understand how decisions are made, in firms as well as policy-making. It could also include historical methods of enquiry that are not currently taught as such to economists. Do you think this could help?

CG: I don't know. I’d have to have more details exactly about what the alternative methods are. In a sense, whatever helps us to understand the economic world better is worth having.

I: What about the core modules there are normally taught in economics degrees, such as microeconomics and macroeconomics? Do you think they can more or less stand as they are? Or would you envision that they include, for example, more viewpoints, or perhaps simply some caveats concerning the generality of their applicability?

CG: Microeconomics, I think, is in less trouble than macroeconomics. I think macroeconomics if anything has gone backwards over the last 20 or so years. The problem is that it’s always easier to criticise than it is to construct. The criticisms that Lucas and others had of the kind of large-scale Keynesian macro models were, I think, absolutely accurate. The problem was that I don't think that the attempts to do microfoundations along the lines that have been pursued over the last 20 years have actually been correct. I applaud the idea but the problem is that the microfoundations weren't properly microfounded. Again, one of the things that I, very strongly, believe is that the proper constraint on us is not income or wealth; it’s time. If you’re thinking about for example rational expectations, I don't think that people do try and find as much information as they can, as is out there, because it just takes too much time.

Under very many circumstances I think that what we do in terms of expectations is either to follow the herd, or to ask other people, or to follow somebody we trust in terms of what we expect to happen. In other words, I don't think that we actually try and make expectations ourselves. It’s too time-consuming. It’s actually rational to try and maximise the utility we get – ‘utility’ is a bit of a loaded phrase – in terms of our total lifetime. That involves playing video games and watching television rather than trying to estimate exactly what we think the rate of inflation is going to be over the next two years.

I: Do you think that part of the difficulties with macroeconomics could derive from the fact that different countries, for example because of their industrial structure or institutional setup, could respond differently to different policies, and these differences may be lost when one aggregates over many countries?

CG: Yes, and certainly so. Again it’s partly to do with issues like trust, and whether one believes that one’s politicians are actually trying to do their best to maximise social welfare, or whether one thinks they’re out there for their own sake. Again, one of the issues that worries me, both again about the recent Brexit referendum and about what’s happening in the politics of America seems to be that there is a general decline in the general trust that most people have of the political class. I think that’s a worrying event. I think it does depend on the institutions, the trust in the institutions that you have, how individuals within a particular community respond.

I: These aspects are, of course, difficult to influence.

CG: Yes, and of course they go back to the wider social sciences. They go back to sociology, they go back to anthropology, they go back to the way that we behave. Again, I think that there has been a sense that economics saw itself as being able to work from first principles to establish towering structures of analytical brilliance without taking account of the wider social and political context. Again, to put the issue fairly simply, not all that long ago, I think it was probably shortly before I became an undergraduate, our subject within most universities was described as ‘political economy’, not economics. I think it would actually be an improvement if we went back to describing our subject as political economy and taught it in that vein. You should know the joke about the economist dies and if he’s a good economist he hopes he’ll get reincarnated as a physicist, or if he’s a bad economist he fears he’ll get reincarnated as a sociologist.

There has been a tendency for that to be true. There’s a kind of physics envy in economics. I think that that has been generally mistaken. It would be much better if we recognised that it probably would have been better for the development of the subject if we had been re-born more as sociologists than as physicists.

I: In institutional terms, and in terms of teaching, this might appear like trying to go back to the time before Marshall established the Economics Tripos in Cambridge as a way to make economics more autonomous. However, since at the time the discipline didn't yet have full autonomy, trying to grant it autonomy in educational terms was probably the right thing to do.

CG: I think that’s right. I certainly wouldn't want to be thought of as criticising the Marshallian approach in Cambridge as such. There was a tendency, having made the subject autonomous, to think that somehow we were independent of, and better than, the other social sciences. I think that it was that sort of arrogance that has been a fault.

I: So this autonomy may have gone too far, turning into a complete separation from other disciplines.

CG: Yes.

I: This brings us back to our discussion of the political and social aspects of money, and especially those relating to power. In your work, you develop an interesting connection between power, optimum currency areas, and what is currently happening in the Eurozone. What is the problem with forgetting the link with state power, especially in constructions such as the European Monetary Union?

CG: Well, there are various aspects of it. I think that those who set up the Eurozone thought of money very much more in terms of the sort of currency-school pure transactions approach and didn't see that this would have wider political and social implications, particularly given the considerable social and other distinctions between the various member states. It was also that there had been a division of view between the French monetarists and the German economists, where the German economists thought that monetary union should really be the final coping stone when you had developed a single community – politically, fiscally, socially, maybe even linguistically – whereas the French monetarists thought that by forcing monetary union you would force a union to come, because there would be so many crises without a full union.

The problem has been that it hasn’t forced the fiscal and political union because the identity of the nation state, linguistic and otherwise, has been so strong, that people have not been prepared to move towards a federal Europe, which has meant that the Euro has moved from one crisis to another, without being any closer now than they were at the beginning of the 1990s to having a single fiscal union, and it has been in many ways a tragedy. I’m not saying that having the EU is wrong, because for many reasons I think that moving towards a greater union in terms of a single trading area, etc., etc., and trying to prevent national disharmony as we saw during the 20th century, is an enormously valuable construct, but it should have been done the German way, where monetary union comes at the end, and not the French way.

The only reason it happened was because Chancellor Kohl, when Germany could get re-unification, needed French support, and the only way that they were going to get support from Mitterrand was if they effectively moved from the Bundesbank being the leading central bank in Europe but having a European central bank, which the French thought that they would dominate. It was a mistake. It was a mistake in some large part because of a failure of underlying monetary analysis. People who wanted to move rapidly to a single currency didn't realise that this involved a whole series of power and social and trust relationships, which were not then and still are not ready to be established within the EU space. So it was a very sad error and again it’s a question of what models you use, how confident you are in your models. The German model was correct, the French model was not correct, but the French managed to get their model into place for a variety of reasons, that seemed to them right at the time.

I: At the moment, monetary integration has been achieved in the Eurozone, but political integration does not seem politically feasible. Do you think one can envision different forms of integration, which can at least make the current institutional setup stable, or is the choice simply between moving forward and moving backward?

CG: Well, that’s a very difficult question and I wish I knew the answer to it. And I’m not confident about what the right answer is. I think that we’ve been on the wrong road, but given that we’ve gone so far down this road, what does one do? A break-up of the existing Eurozone would at this point of time be horribly dangerous economically. On the other hand, it’s not a structure that is actually working. So where does one go? That’s the sort of issue that, thank God, I don't have to advise on, and it is horribly difficult.

I: Thank you very much, Professor Goodhart, for your thought-provoking reflections.

CG: Thank you.

(End of recording)