KEY:

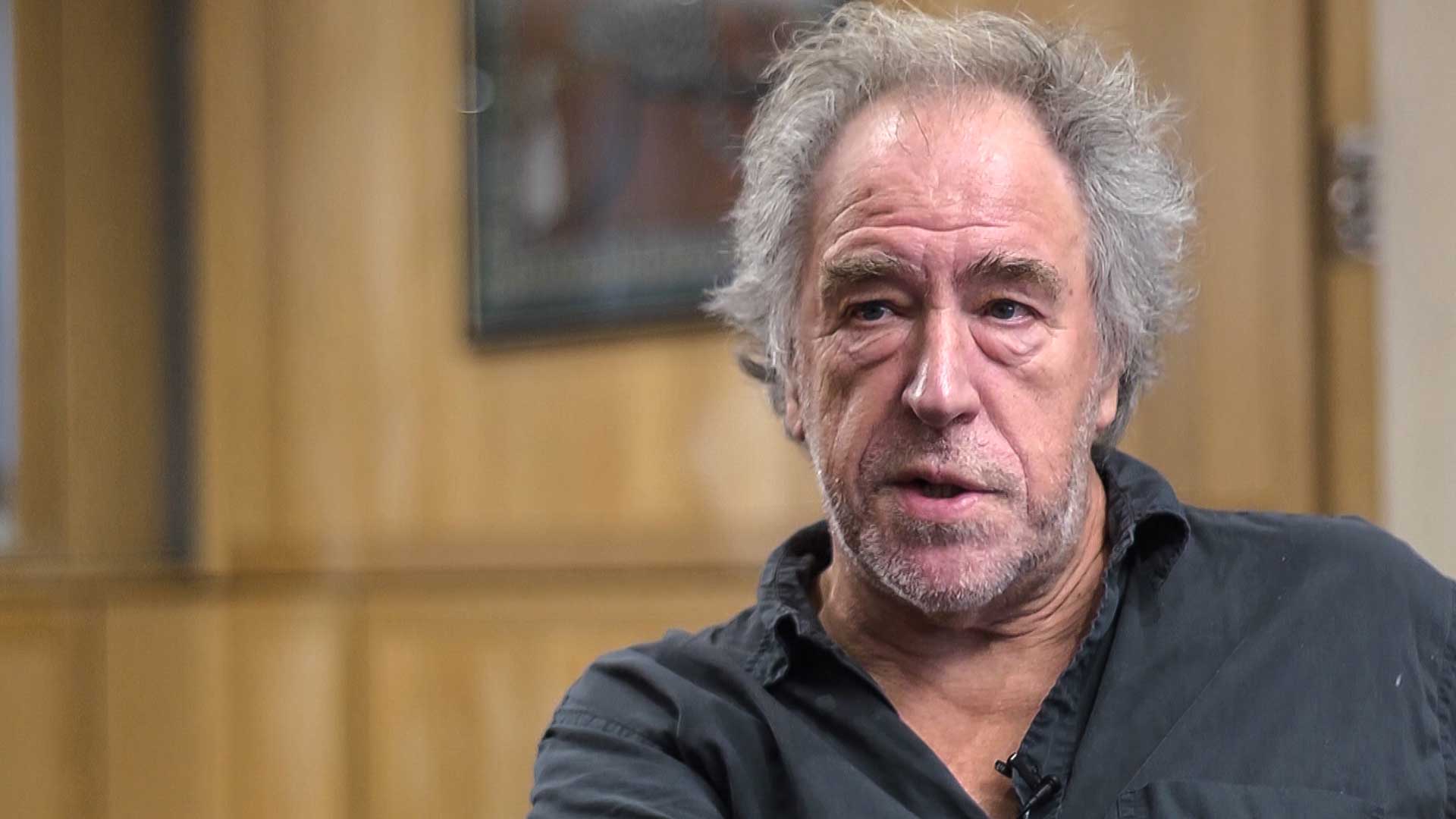

I: Interviewer: Ivano CardinaleTL: Tony Lawson

I: We are with Tony Lawson, Professor of Economics and Philosophy in the Faculty of Economics at the University of Cambridge. Tony, thank you for agreeing to participate in this interview series organised by Economics at Goldsmiths and the Independent Social Research Foundation. I would like to start the interview from your reflections on the current state of economics. How would you characterise it?

TL: Well, it’s in a bit of a mess. Mostly, I would say, it’s irrelevant. It does not attempt to address the way the world really is. It’s much more concerned with conforming to an image of science which, as it happens, is not a good image of science, leading very many modern economists to proceed in ways that are mostly irrelevant.

I: Why is it irrelevant? Is it because of the features of social reality?

TL: Yes, precisely. Let me take the opportunity to say the problem stems from the use of certain methods. But I’m not criticising the methods, I’m criticising the inappropriate use of them. Economists choose the methods in an a priori fashion. I mean, to be blunt, or specific, they use methods of mathematical modelling whatever the context. In any other discipline, they start with a problem and the context, they look at the nature of the problem being addressed, and they design methods to fit the task, the world, the context they’re dealing with. Economists, for the last 60 years, have started from the assumption, ‘This is the method. Give me the problem.’ If I said to you, ‘I’ve got a task. Will you come and help me? Bring your tools,’ without telling you what tools to bring, I mean, first of all you’d probably say, ‘Get lost,’; but if I offered you a few million pounds, you’d likely say, ‘Well, what tools? What’s the task? What do I need to bring?’

Economists don't ask that question — ‘What is the nature of the task?’ For the last 60 years, they’ve insisted on the same type of tool for all jobs, all applications. Forms of mathematical modelling. As it happens, these methods don't fit social reality very well at all, they are mostly inappropriate to its analysis everywhere, given its nature. So, this is the problem. It is firstly a failure to consider the nature of context and say, ‘What are the appropriate tools?’; and it is secondly, in erroneously adopting a universal approach a priori, they have relied upon tools of a sort that, as it happens, actually are hardly useful at all.

I: Why is that the case? What is social reality like?

TL: Well, that’s a long story. The sorts of methods mathematical economists use presuppose closed systems; worlds in which correlations, event regularities occur. Such regularities are guaranteed in conditions where economic agents, whatever they are, conform to acting as isolated atoms. By atoms I mean they have the same independent invariable effect whatever the context. Social reality is just not like that. Its open. Rather than agents being fixed, they’re in process. Rather than agents being isolated, as social beings all are relationally constituted.

I: An economist committed to mathematical modelling might respond that those models could be an approximation of reality. What would you respond?

TL: I’d say they are not, not in general certainly. Fairly clearly, closure is not a good approximation to openness. Fixity is not a good approximation to continuous transformation. And being independent and isolated, is not a good approximation to being relationally constituted. In a context of 60 years of pretty much continuous failure of the discipline—failure of models to explain, to predict, to arrive at real insight—this inability even to approximate the nature of the phenomena of social reality is the explanation of the irrelevance of the discipline’s substantive formulations and the lack of successes at providing insight.

I: Do you think that mathematical modelling is generally unfit to understand social reality, or are there situations or ways in which it could be relevant?

TL: It could be relevant if, where or when social reality contingently conforms to the underlying preconditions for modelling to be appropriate — to worlds of isolated atoms. For example, driving in rush-hour traffic; people pretty much are isolated and atomistic. Or consider the demand for heating and electricity in Alaska in the middle of the winter—there’s not a lot of choice in it. Such situations are rare. But you are asking the right question. The question is not, ‘Are these methods in or these methods out?’ All methods should be on the table, as it were, but one should start from an examination of the nature and context of a problem. What are we looking at? What is the nature of the phenomenon we’re dealing with; and, if you like, are mathematical methods appropriate in these conditions? It’s an empirical question.

I: Before we move to the approach that you propose—the ontological approach—I would like to touch on something related to our discussion so far. You distinguish between an orthodox or mainstream economics on the one hand and the label of “neoclassical economics” on the other. They are often equated but you say that they are not the same thing. Why you think they’re different?

TL: I think the modern discipline is dominated by members of a particular group or club. We all know them when we see them in action and they know anyone who’s not a member. The one thing that characterises this group is the emphasis on mathematical modelling. So, I think there are all sorts of reasons to say the nature of the modern mainstream is just this emphasis, which is more or less an insistence, on certain methods— those of mathematical modelling. The term neoclassical is something else. Its meaning is rarely given or clear. X uses it to criticise Y. Y uses it to criticise Z; and no one defines it. If you go back to the coiner of the term, Veblen, he used it to indicate those people who accepted a realistic ontology or account of the way the world is— characterised by evolutionary cumulative causation—but used methods inappropriate to it, that presupposed a very different unrealistic ontology; neoclassical was essentially his name for this inconsistency.

So, if we were to apply that term and Veblen’s arguments to modern economics—and there are some reasons to do that, but it takes a long time to give them—it would apply mostly to self-styled heterodox economists who persist in using/use methods of mathematical modelling. But I don't think it is especially helpful or charitable to name a group, a school, on the basis of an inconsistency that its members are largely unaware of committing. So, ultimately, I suggest we drop the term ‘neoclassical’. The ‘contemporary mainstream’ is good enough for those that dominate.

I: So your division between mainstream and non-mainstream approaches is based on methodology. In other words, you think that the mainstream is defined by the methodology that is considered acceptable.

TL: That’s right. The mainstream is defined in principle by an emphasis on applying a narrow set of methods, those of mathematical modelling, whatever the context. In accepting this principle its advocates are forced into working with a particular ontology, whether they recognise it or not: to presupposing worlds of isolated atoms. Thereafter they are reduced to focusing on theories, or formulations of theories, that can be transformed into the world of isolated atoms. In essence, human beings have to be turned into atoms. The obvious assumption to use in order to effect this is that we humans are all super-rational; we don't make mistakes. Situations are devised wherein, relative to the notion of rationality specified, there is a unique optimum, and the presumption is that any model agents, being rational, would ‘end up’ there.

Heterodoxy is something else. Its participants put much more emphasis on at least seeking to be realistic. I do think underpinning most of the different schools within heterodoxy are more realistic ontological presuppositions; these, if not always explicitly made clear are usually close to the surface. Another difference is that even when heterodox economists use mathematical modelling, they’re far more pluralistic about it. They are willing to engage with people who don't. They’re willing to say it’s one method amongst others. So, pluralism of method is essential to heterodoxy.

I: As a response to this characterization of mainstream economics, you advocate a turn to approaches in which the nature of social reality is taken seriously, and appropriate methods are defined. What would this ontological turn entail, in the way we study economics and understand reality?

TL: Well, an ontological turn, first and foremost, just means considering in a systematic fashion the nature of what we’re dealing with. It’s so obvious it shouldn’t need to be said, in my view; but it’s missing. It used not to be missing. Marx, Keynes, Veblen, Marshall, all made ontology central, whether they used the word or not. Since methods of mathematical modelling became dominant, there’s a sense in which, for its practitioners, ontology is defunct. Ontology enables us to determine the sorts of methods that are likely to be appropriate to particular tasks. But, in mainstream economics, the choice of methods comes first, and so one central role for ontology disappears. So, if we have a turn to ontology, we start asking the question: ‘What are we dealing with?’ Most generally, what is the nature of social reality? How do social phenomena exist? Then we can pursue more specific questions, like what is the nature of the particular entities, etc. that we are dealing with? Money, corporations, technology, gender, care, etc.

Then, of course, we fashion methods as we go along. Just as they do in the non-social sciences. To take an example, according to the best theory of particle physics, particles have no mass, and that result needs an explanation. Higgs came up with his theory of the Higgs boson particle or field around 50 or 60 years ago. The theory itself bore implications about the sort of tool that could be used to test it. They required something like a particle accelerator, such as that at CERN. So, they awaited its construction; the method of testing follows the nature of theory, or its posits. In economics, the theory follows the method.

I: Do you see social ontology as a first step that is then followed by other kinds of investigation? Or is ontology a way of knowing reality in its own right?

TL: Well, it’s certainly all about investigating the nature of reality. But it needn’t be a first step. Indeed, there is no first step. It just has to be a step. I see substantive theory, ontology, epistemology, and method choice going hand in hand, each influencing the others. You start where you find it best to start. I think typically this is with a puzzle. But a puzzle pre-supposes a theory and understanding. You start with some kind of contradiction and you decide, ‘Well, how do we resolve this?’ You may soon say, ‘What’s the nature of the stuff we’re dealing with? You might need ontological analysis; or you may already have that answer, or a relevant insight, and go straight to questions of method. It all depends. So, what I’m saying with an ontological turn, is that ontology needs to be included explicitly in a sustained fashion. Not that it comes first or dominates.

I: When performing an ontological analysis, does the analyst normally start from the common sense understanding of the problem at hand, which then gets refined and, if necessary, contradicted, and so on? Or does existing theory also play a role?

TL: I think it depends on context. I have such a low opinion of existing economic theory that I would say, typically, not from economic theory. But we’re all theorists. To get from wherever we started from to here today, we use social theory. We have theories about everything we see around us. We don't start from nothing, but, yes, we start from whatever understandings we take as grounded. They’re like our nominal essences, if you like, and then we work out what’s behind them. So, we may have a rough understanding that dogs bark, so we look around for all the creatures that go around barking, and we think, ‘This is our starting point,’ and then we try to work out, ‘In virtue of what are these things dogs?’ We might get at their genetic code. But we might find on route that other things bark or not all dogs do bark or whatever. So, we make refinements. So, we start with the level of understanding we have.

I: So, for example, if we were to study money, as you have done, would we start from existing understandings of money, probably also considering how they relate to each other and whether they explain money well enough?

TL: Yes. There isn’t a formula. If we start from the appearances of money, the nominal essence, the way money seems to be, we’d probably start with the fact that it’s used as a general means of payment, to discharge debts. We’d probably start too from the fact that it has purchasing power, that we can go along and offer it to people and get into debt with them. Then we ask the question: ‘In virtue of what does something have these powers?’ That something would give us the nature of money. En route, we could well look at existing theories, and if we did, we’d find there are theories called commodity theories of money, theories called credit theories of money, and so on. We might decide that one of them explains the phenomena adequately, given whatever evidence we use, or it doesn't. As it happens, I think both commodity and credit theories can be shown to be special instances of the same general theory of money, but that’s a long story.

I: The general theory of money that you propose emphasises the role of positioning.

TL: I argue everything in social reality is constituted through processes of positioning. We are so now, for example. You’re constituted as the questioner. I’m constituted as the interviewee; the person being interviewed. There’s a ‘camera person’ standing next to you and there’s someone else in the room positioned with a different set of rights and obligations, performing some other kind of function. Those objects over there are constituted as tables or windows and so on. Everything is constituted through positioning. Money is no exception. It’s constituted in part in relation to us, or the rights and obligations of community members are constituted in part in relation to it, in the sense that if I have money in my pocket, I have the right as a member of the community to use it to discharge a debt. So, it’s positional and it’s related to everyone and everything else in the community.

I: So, as far as I understand, there are features that an object needs to have in order to count as money, but then it is not the object in itself that matters, but its positioning.

TL: I think it’s more that it’s accepted as the object that can fulfil these roles, so as a means of payment, for example of payment of tax. It’s quite contentious whether the stuff itself that is so positioned can be any item, or whether it must already have value. What is clear is for a money stuff to work as money, it has to be trusted, has to be liquid. People must be able to feel that if they accept it, they can pass it on to cancel debts in the future themselves. I think that sort of trust usually requires that the stuff positioned as money is already a form of value. But that’s contentious.

I: This interview series aims to relate research and teaching in economics to the existence of different traditions of economic thought. Is there a relationship between social ontology and the history of thought? For example, is there an interest in reconstructing the ontological stances of past economists?

TL: Social ontology per se is the study of the nature of stuff. Whatever the focus it’s impossible to avoid ontology. The only question is whether it’s explicit or implicit. Even mainstream modellers have their implicit ontological presuppositions, which is that the social world is everywhere composed of sets of isolated atoms. So, I think it is bound to be useful to view different strands of history of thought in terms of the ontological presuppositions of the protagonists. It is always significant. If I was teaching history of thought, I’d certainly point out that out. If we take say Marx’s Capital, he starts with the commodity, but not just the commodity under any aspect, but the nature of the commodity: and he asks how do we explain its nature and he goes into the nature of value, the nature of money and the nature of labour power.

Keynes starts his Treatise on Money with a chapter—he calls it a book—called ‘The Nature of Money’. He starts with ontology. Veblen does ontology through and through. His definition of neoclassical economics is based on ontology. His call for an evolutionary economics was based on ontology. Hayek started out trying to justify equilibrium economics and went to his notion of spontaneous order. It’s all ontology. It’s all about the nature of social order and social reality. So, I would certainly do history of thought ontologically if I was to teach it, but then I think ontology enters everything.

I: For example, how would you characterise Marx’s ontological stance on society or capital or value? Do you think it’s useful to do that?

TL: I would say that Capital is a book precisely on ontology. As I’ve just said, it starts with the commodity. He says, ‘What is a commodity? It seems to have a usefulness, a use value. This is unrelated to its price or its exchange value. How do we make sense of this?’ and that leads to the question, ‘What is value?’ That leads to the question, ‘Where does value come from?’ and, ‘What is the nature of the source of value?’ Labour power or whatever. It is ontological through and through. But his broader question is, ‘What is the nature of this relational, processual, totality in motion that we call capitalism?’ So, the whole thing is ontological. The details of Marx’s ontological position are certainly something we can argue over. I’m not claiming that he was wholly consistent either, but ontology is systematically there. He used the word metaphysics. Veblen also used the term metaphysics. But both Marx and Veblen meant by metaphysics what I mean by ontology.

I: So is it useful to know the history of thought in order to perform the kind of ontological analysis that you advocate?

TL: Yes.

I: Is there a tension between starting ontological analysis from common sense understandings or from available theories?

TL: I’m very sceptical of common sense but you can start wherever you like. Capitalism has its history and its early history led to its later history. So looking at people who study its early history can provide relevant insights. The question then becomes, ‘Are these early insights still relevant? How deep were they? Are they essential to capitalism throughout its different forms, or are they now redundant as claims about the modern world?’ Yes, so a lot of it is potentially relevant.

I: When you say you’re sceptical of common sense explanations, do you mean that they are based on a pre-scientific understanding that needs to be questioned? Or are there other reasons?

TL: I guess I said that because -- I won’t name any but -- some heterodox economists say that in rejecting mathematical economics, the alternative is a common-sense approach to economics. That bothers me a bit. I think that common sense often stands in for the trivial, the unexamined, the uncritical, the everyday. What’s really missing from modern economics is long-term commitments to projects of understanding deeper issues, to pursuing specific projects or questions systematically. Marx spent his life studying the nature of capitalism. Hayek spent most of his time studying social order. Keynes, Veblen, Marshall, whoever, they had long-term projects, Schumpeter especially, long-term projects that took them their whole life.

These days, economists work on topic X one week, topic Y the next, the topic Z; I’m exaggerating a bit, but claiming it is all common sense makes it seem just too obvious, too quick, too easy, leaving the deeper issues under-examined.

I: We could say that common sense is itself a social entity, which could be examined as such.

TL: We can.

I: In other words, one cannot take common sense as a monolith: it has its own stratification.

TL: That’s right. Well, again, ontology comes into everything. I mean, some of what most people call common sense, we’ve had a long time learning anyway. So, it’s not like you just look and see and know. But if it was the case that what we take to be common sense was enough for understanding, then fine. But, typically, this is not so. Take money. If you ask people, ‘What is money?’ I think the answers you get would not be very insightful. I think money is a social relation, a particular type of positioned social relation. But if that’s right, it’s not common sense, and it is very difficult to convince other people of it.

I: It is probably worth clarifying that, when you advocate realism, you are not referring to common sense, but to a much more specific definition of realism.

TL: Yes. Let me qualify what I said on common sense, though. I don't want to impose or exclude anything. The point is to bring in ontology in an explicit and systematic way. And if an understanding of something requires going way beyond what we call common sense, if it requires an understanding that’s seemingly perverse, and money certainly throws up many perverse aspects, then so be it. It takes what it takes.

I: One could argue that ontological study could open the way for a variety of economic approaches, or a variety of schools or ways of doing economics. Is that how you think economics should look like—as a variety of schools or approaches or research programmes that are aware of their ontological presuppositions, but then go their separate ways? Or do you think there is a unified way to do economics?

TL: My assessment is that most heterodox groups are each best identified or distinguished through a tradition-specific focus on issues that fairly clearly reflect ontological presuppositions and concerns, and indeed a shared set. Institutionalists, following Veblen, are very interested in both evolutionary change, and things like institutions that bring stability within change. So, in evolutionary economics a focus on process and stability is fundamental. Post-Keynesians are very interested in uncertainty. Uncertainty basically derives from the openness of social reality. So, it’s an ontological presupposition of openness that conditions their focus. Feminists are especially interested, I believe, in relationships. Relations of care, oppression, exploitation, etc. It is an ontological orientation of relationality that is fundamental here. Marxian economists focus on the relational totality in motion that is capitalism. So, ontological categories like relationality, openness, process, totalities are key to identifying the various heterodox traditions.

I believe the just noted ontological categories are everywhere relevant, each being fundamental features of all social phenomena. So, I see the separate heterodox traditions each as a division of labour looking at the same basic social reality from a particular perspective. Implicitly at least, they agree more or less on the nature of social reality, and are divisions of labour within the study of it.

But, in truth, to take your question slightly further, I don't think there’s a non-arbitrary basis for having a separate discipline of economics anyway. Because once you look at the nature of social reality, it’s found to be the same basic stuff we’re dealing, whether viewed from within sociology, politics, anthropology, whatever. We’re all divisions of labour in relation to a specific field of enquiry: social reality. So, just as we have divisions of labour within economics, I think economics is just a division of labour in a broader social science, with economics’ own division being about the material conditions of wellbeing or whatever.

I: In the final part of the interview, I would like to touch upon economics teaching, which is one of the key themes of this interview series. How were you taught economics?

TL: I wasn't, really. My experience of being taught economics has been very limited. In retrospect, I’m pleased about that.

I took a first degree in pure mathematics. I became involved in student politics. Instead of continuing with mathematics as I had intended, I changed and went to the LSE to do a masters in economics. However, what I found was people teaching me IS/LM curves, Robinson Crusoe analyses, excuses to do mathematical modelling. After a short period, once I’d learnt the jargon etc., I looked at past exam papers and I realised I could in essence answer the questions already; it was mostly mathematical manipulation. So, I didn't really pay much attention to the course. Instead, a year later, or whenever, I went to Cambridge and took up a PhD, more or less by accident, and in those days you didn't need much education in economics to do that, sadly. I started a PhD, and within a year or so they gave me a job. So, I haven't really received a good deal of economics teaching along the way.

I: How did you become interested in developing a social ontology research programme?

TL: It happened, in effect, on my first day of economics lectures. This was when taking the Masters at the LSE. I can remember listening to all sorts of theories and assumptions being set out, and being associated with the names of different economists, and then I put my hand up and said, ‘Okay, you’ve told us about the model of X and the model of Y and the model of Z, but what really causes some phenomenon?’ The lecturer just looked stunned, as if to say, ‘How impolite can you be? You don't ask that question.’ I looked around the room and a soon-to-be friend of mine who was on the same course, Mary Farmer, who unfortunately died far too young, she was a sociologist, said to me, ‘Economists don't care about the real world. They only look at models.’ She was on the course to study economists for her proposed PhD in sociology. She called them ‘The Economics Tribe’.

So, it started at that moment. I thought, ‘Why? Why aren’t economists interested in the real world? Why do they work only with these models?’ which to me seemed, right from the outset, irrelevant. So that’s when I started doing ontology in effect. I said to people, ‘These models, why do you use them? They’re clearly unrealistic. They’re clearly not very relevant. They’re not going to help us understand,’ and the question that came back was, ‘So what is relevant? What is the social reality really like then?’ That’s when it started.

I: Philosophy of science played an important role, I think, in your development of ontology. Was it because it helped you reconstruct the reasons why you found economic theories not suitable for ontological investigation?

TL: Yes. I read around. My intuition was that doing economics was a bit like someone saying, ‘Here is a feather or a hammer. Go and cut the grass with it.’ I just felt it wasn't appropriate. And yet there was a whole economics profession building these models, and so I supposed too that there must be something to it. I was asking myself: Am I being really naive here? ‘What am I missing?’ ‘What is science?’ What is method? How do we deal with these things?’ It was all new to me. I come from a pretty poor background, with limited education. Mathematics got me to university. I hadn't studied these issues. I was aware that I was probably ignorant. Well, I was ignorant of so much. So yes, I went and read lots in the philosophy of science. I followed my own route. Modern day philosophy of science, Aristotle, all sorts of people. But I was mostly reading the literature in order to resolve the questions I had. I didn't read philosophy for the sake of reading it. I read widely because I had my own project and I wanted to find answers.

I: This is interesting—it seems a highly ‘unscripted’ process, with a lot of exploration. Was that also made possible by wide margins of institutional freedom?

TL: Yes.

I: Perhaps also because PhD programmes at the time were less structured?

TL: One day I saw an advert in the newspaper. It said, ‘Wanted, someone to spend their life criticising economists and arguing for a turn to ontology.’ So I applied. …. Yes, you are right of course. I had lots of freedom. And my path was unstructured and indeed unplanned. In fact, when I was a student, my put-down for friends who didn't want to come out drinking or whatever was to call them ‘academic’, I never thought I’d become one. My path was unscripted and unexpected. I was lucky. I got into places at times when there were grants. Mathematics I was good at. That became a passport into other things because everyone gave a place to a person who’d done well in mathematics. I got a job in Cambridge. There was a grant going spare. I took it. My supervisor -- Angus Deaton -- left. They gave me his job. It was just an easy path. I didn't choose it. I wasn't looking for it. I didn't expect it, but it happened. The one thing that mattered to me was to be relevant. So, when opportunities came my way my primary thought was, ‘If I’m going to do this, I’m going to do things I believe in.’

So, I spent my time questioning, ‘Why do you do this? Why do we do this? Why? Why assume that?’ All the way along, I found people didn't have answers because they didn't ask the questions. Somehow, they just took it for granted that that’s the way to do it. So, I pretty much made it up as I went along.

I: How do you think economics should be taught?

TL: Obviously with a greater concern for relevance. However, I do not think what is happening at present in the name of relevance is especially good. There are many concerned individuals seeking or claiming greater relevance, but really only allowing the sorts of changes that, given where the problems lie, result in essentially more of the same. In particular, a few experts are currently writing alternative textbooks, but, in this they are merely focusing on slightly different models, perhaps slightly simpler models, albeit using them to address slightly different questions.

The whole system, the whole of academic economics needs to change, including, obviously, what is taught. The central problem just is this emphasis on mathematical modelling. I disagree with many other heterodox economists, who think the primary problem is political ideology. I think it’s methodological ideology, according to which mathematical models are the obvious tools to use. It’s a form of blinkering. But I think once the blinkers are removed, everyone will be better placed to contribute to teaching.

We always start from here. If it were to happen now, current mainstream approaches would probably become options because that’s all that the current group of academics can teach, but with blinkers removed everything would, I believe, quickly evolve. We don’t need leaders or textbooks. We just need to free ourselves of the blinkers. Then everything can evolve in the manner of any other discipline, according to projects concerned to understand the world and make progress. Our teaching will be informed and take whatever path is found most useful in the circumstances. There isn’t a blue print. Economics would become a discipline in process that adapts to current understandings, topics considered most important, the skills of those present in any department, and student interest. It would be driven by all these things.

But maybe the question you’re asking me is: ‘what would I do if invited to start a course tomorrow?’ Well, obviously, ontology would be there. I just do not see how you can teach any discipline without talking about the nature of the stuff you’re dealing with. It’s unimaginable that you could teach a course in physics without ever approaching questions like, ‘What’s the nature of heat? Of light? Of quantum fields? Of mass? Of particles’ Ontology would have to be a part of it. But the starting point would be general understanding.

Of course, substantive theories would change too. If I had, off the top of my head, to name a text I would choose as a backup for a more substantive course, I’d probably use

The Ragged-Trousered Philanthropists.

1

It’s a novel but I’d go through it chapter-by-chapter and use it as a device to raise questions in economics. But that’s off the top of my head. I’ve been in the Cambridge faculty for 200 years, or so it feels like, and they’ve only let me teach methods of mathematical modelling; the question has never arisen.

I: Is there anything you would like to add before we end the interview?

TL: One thing I think it’s important to recognise is that ontology is not something mysterious. It’s not something that only goes on in philosophy departments. In fact, social ontology doesn't formally happen there very much. Implicitly though, we all do it. Walking down the street, you’ll act differently according to whether the thing in front of you is a lamppost, a person, an elephant or whatever. You just react differently. Arguing for an ontological turn is not about recommending a turn to something that’s mystical or for the experts. It’s just about making explicit and systematic what we do each implicitly all the time. If you’ve got a problem in the house or in the garden you choose tools appropriately. You don't just take the nearest tool or the tool you like best and go and try it out for everything. You condition your choice according to the nature of the task.

It’s really just about being explicit, systematic, sustained about what’s always involved. But, even so, I think an ontological turn in economics in the sense of rendering explicit what is already there but implicit would have radical consequences. It means, I think, that most of the contributions in modern economics would be seen immediately to be mostly necessarily irrelevant. The methods of mathematical modelling just are not very appropriate for social analysis, and this would be obvious to all.

So, the proposal of an ontological turn is not one without likely consequences, but the proposal is not a big deal in itself; the point is just to start taking notice of the nature of stuff we deal with.

It’s not an anti-methods proposal. It’s a pro being critically aware proposal. I think that’s important. I’ve already stressed it, but I will stress it again. This is not an anti-mathematics stand. It’s not an anti-science stand. In fact, I think it’s a pro-mathematics and a pro-science stand. It’s an anti-mismatch stand. An anti using the wrong tool for the task, stand. Or, more positively, it’s pro making sure that whatever your task, you’ve got the right sort of tools for it. If in certain situations they turn out to be mathematical in nature, fine. But, typically, they won’t be, in the social realm.

I: Anything else?

TL: Not that I can think of at this moment but as soon as this is over, I’ll think, ‘What about that, that, that and that?’

I: Thank you very much for the interview, Tony.

TL: Thank you.

(End of recording)