KEY:

I: Interviewer: Constantinos RepapisR: Respondent: Professor Julie Nelson

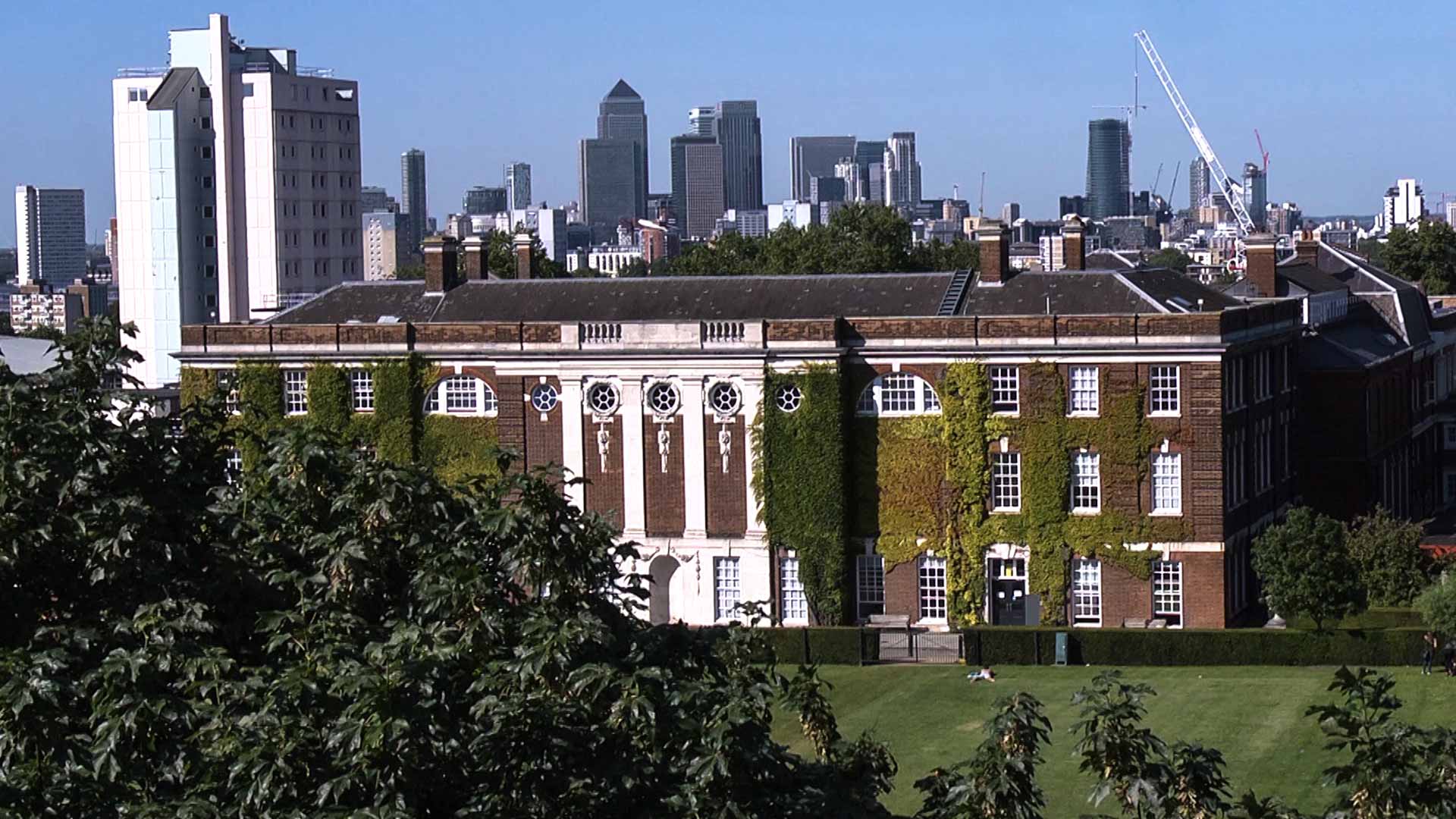

I: Professor Nelson, I’m very happy to welcome to you this series by ISRF and economics at Goldsmiths. Let me start with a general question, what is feminist economics?

R: It covers a wide variety of areas, only some of which I work in myself. Marianne Ferber and I had to come up with a definition at one point because we were doing a little survey. We called it ‘work having to do with the economic roles of men of women that has a liberatory bent’--that is, that doesn’t just reinforce gender stereotypes—‘and work on the definition and methodology of economics that shows the gender biases there’.

I: What do you think is different in the methodology of feminist economics to other types of economics?

R: The methodology tends to be a lot wider. Focussing on applying a specific set of tools that you learn in graduate school to whatever problem comes up often ends up forcing a problem into an artificial state in order to be analysable by those models. Feminist economists, for the most part, are willing to look across a broader variety of methods. So, we have people who do standard wage equation econometrics. We also have people who do interviews, or use qualitative data, literary analysis, or combinations of all of this. I recently worked on a project that combined statistical meta-analysis with research in philosophy and linguistics, in order to understand how people were interpreting the way in which the results of the empirical analysis had been phrased. So, I think we have a bigger toolbox of which more standard models and methods are only a small part.

I: You mentioned two things in your answer. One is philosophy and linguistics, the other is different perspectives within the profession. In your work and in feminist economics as a field of study generally, how do these things combine? Are they reinforcing each other or are these two different ways of doing research?

R: You mean different perspectives in economics? I’m not quite sure what you mean.

I: I mean between different perspectives within economics, compared with different perspectives from outside the discipline.

R: There really is no place training feminist economists: They come through various kinds of training with various kinds of slants. The bulk of economists come through a fairly mainstream training. In the US, UMass Amherst has long taught both mainstream and Marxist schools. It was one of the places that tolerated some of the first feminist economics work, so some people came out of there. When we created an international association, we called it the International Association for Feminist Economics, and we explicitly did that rather than saying ‘of’ feminist economists, because we wanted to encourage people who are maybe in public policy or sociology or activists on economic issues to also come together to discuss these things. But we do have people with Keynesian or post-Keynesian backgrounds. We also have one libertarian Austrian type feminist economist, as well as people from Marxist and institutionalist economics, socioeconomics, and ecological economics. In short, people come from various areas.

I: Do you think these people bring different methodologies? Because you spoke about that; people from different perspectives within economics compared to interdisciplinary work. And if you are a feminist economist, how do you really sort out between these methodologies? How do you know how to do feminist work?

R: My approach to doing social science is it should be systematic open-minded investigation about a problem. If it’s not about some kind of problem--or to put it another way, if it’s just a mind game that you happen to enjoy doing--I don’t see what the social usefulness of it is. So, if you’ve got a problem you want to address, then you have to look around for what tools seem to give you the most insight while being the least distorting. At least, that’s the kind of guideline I’ve used for my own work. For younger economists, there’s still very much the pragmatic advice that I give, which is ‘Get your dissertation and some publications’. You have to pragmatically choose some of your methods for that. But I hope it doesn’t stop you from thinking more broadly in terms of longer term life work.

I: The focus on realism is definitely a very interesting way to sort out the methodology. You start from a problem you identify from reality instead of a preconceived methodology to deal with existing problems.

R: I actually associate it with institutionalist economics and with American pragmatist philosophy, John Dewey and some of those folks. I actually went to the University of Wisconsin-Madison, which was a big place for John R. Commons and institutionalism. John R. Commons didn’t leave a cogent theory for institutionalists to follow. His contribution was more about the pattern of his work which was to find a problem, bring together the people that might know something about it--even if some are workers and some are capitalists—and get them talking about it. So, it’s different kind of approach.

I: You spoke about different schools within economics, do you think some have integrated more successfully feminist perspectives in the way they do economics compared to, let’s say, the mainstream school?

R: I would say the mainstream has integrated very little. I actually got asked to do a book review for the

Journal of Economic Literature, which appeared in the last issue.

1

Every once in a while we get a little bit of something in the main mainstream journals, but there’s certainly no feeling among mainstream economists that feminist economics needs to be taught. I would say that feminist economics were welcomed more quickly by a lot of the heterodox schools, by socioeconomics, humanistic economics, Marxist economics, and others. I think the macro people doing post-Keynesian economics may have been open to some feminist work a little bit later: they initially didn’t see feminist work as relevant. There have also been some economists who call themselves ‘pluralist economists’ and include ‘feminist’ whenever they list various schools but who I don’t think have actually read this material. When they go to talk about it, they talk about it as if it’s the study of women and women’s issues and have not looked at the feminist methodological critiques. So, they offer friendliness but not necessarily knowledge or the willingness to spend time learning what we’re about.

I: Both from the mainstream and from some heterodox schools, you mean?

R: Yes.

I: This leads me to a question I wanted to ask you, which relates to your essay on ‘Feminist Economics at the Millennium: A Personal Perspective’.

2

In the essay you mention that you were an undergraduate economics major in the early seventies and you were shocked by the fact that a lot of things were mentioned; on low wages, on occupation segregation by sex; and at the time theories simply discussed these issues away. What has changed and what hasn’t since that time?

R: Well, yes, a lot of us started, in feminist economics, with critiquing models of labour markets and the household pioneered by Gary Becker. A lot of those models seemed to explain away and reinforce sexist behaviour. They claimed that women were supposed to specialise in the home because of comparative advantage, that women would get lower wages in the workforce because of lower human capital, and various other things. Times have been changing since then. Women now earn more college degrees than men, so it’s hard to fall back on that ‘women are less educated’ reason any more. For a while there was a lot of progress raising issues of discrimination in economics. Some of my feminist economics colleagues did an analysis of the use of the word ‘discrimination’. It kind of peaked in the late seventies and eighties and has been on the downswing in economics journals ever since. It’s not as hot a topic: People tend to now refer to an ‘unexplained wage gap’ that could be due to lots of things, and are less likely to mention discrimination. About household models, there was the introduction of bargaining theory, which at least recognized two active people in the household, not just a household head. There was some amount of progress, and some amount of listening across disciplines to other things about households. On the other hand, I think there’s been some swing back. Some of the work I’ve been doing in the last couple of years has examined what seems to be a resurgence of stereotyping about women and women’s abilities. One indicator of this was a statement by Larry Summers, the economist, when he was President of Harvard. He said at an MIT conference that maybe one of the reasons there are fewer women in science is that women are not as able in doing that. This was a pretty shocking thing to come out of a university president! Imagine what the female science students at Harvard felt like, feeling their president undercut their abilities. So, he got in a lot of hot water for that. The field of behavioural economics is also fairly new. Some of it I think is pretty good, though some of it I think takes credit for reinventing psychology--things that social psychologists and psychologists have been doing for years. But there’s been some literature coming out of behavioural economics saying ‘Well, women are less competitive, women are more risk-averse, women are more altruistic.’ There are claims that that then explains things like the wage gap and the lack of women in leadership positions. So, I think there’s been some backlash swing. My research during the last couple of years looked at phrases like ‘women are more risk-averse than men’. Philosophy and linguistics tell us that they’re considered to be generic statements about categorical differences, like ‘ducks lay eggs.’ Actually, only a minority of ducks lay eggs--only the mature females! Most ducks don’t lay eggs. So when people hear ‘Women are more risk-averse’, people tend to think of that as categorical--women over here, men over there. In my meta-analysis, I looked back at the statistical data on which this claim was based and the two distributions are almost entirely overlapping. There is at least 80%, sometimes 90 or 96% overlap between the men’s and women’s distributions. There may also be tiny, perhaps statistically significant differences in the means of the distributions, but men and women are really a lot more similar than different. Yet, if you read the titles of certain books or articles, you would be getting a big misperception.

I: This leads me to a question I wanted to ask you. In your work, especially in your work in the 1990s, you were very critical of the rational choice model as supposedly gender-neutral but not in reality. And I was going to ask you whether behavioural economics, which is now an increasing part of the field, has to some degree integrated feminist perspectives. You’ve answered this to an extent, but going back to your work, do you think this has been a positive change or a negative change or a neutral change?

R: I think behavioural economics has good aspects and bad aspects. The part that I think is positive and does parallel some of the critique in feminist economics is the critique of rationality. Our brains did not evolve to solve logic problems. Our brains evolved to keep us and our species going and tend to react in ways that do not come from mathematical optimisation problems. And so there’s been some looking into that. Two things I see as more negative. One is that behavioural economics tends to focus on problems of individual choice and I think that is much too narrow a definition of economics. Inequality, poverty, climate change--there may be some individual choice aspects of those problems, but I also think economists need to be concerned with a lot of these bigger economic problems that go beyond individual choice. The other part is that some of this has a conservative, confirmation bias, sexist stereotyping bent. As I mentioned, there are studies that purport to say women and men have very different socio-cognitive abilities and preferences, which turn out to be quite unfounded.

I should add one more point about behavioural economists. They have critiqued the idea that the agent is rational but they haven’t critiqued the idea that the economist is rational. So, they tend to still believe in the power of the models and their own objectivity. In this work I’ve been doing on gender and risk-aversion, I’ve also been coming up with very blatant examples of confirmation bias, economists ‘finding’ exactly the belief they had in the beginning, really in spite of the empirical evidence that they had gathered themselves.

I: Your focus is a very deep methodological focus on how people conduct research, and therefore their own bias in this. It reminds me of something that you said in one of your pieces, that you identified both as an economist and a feminist. What do these dual roles mean? Have they integrated over the years into one role?

R: I’m a social scientist at heart. I want to figure out what’s going on in the social world. As I said, feminist economics as a whole is a pretty big umbrella organisation and, as a social scientist, I have a little bit less patience with some of the critical literary analysis because at the end of the day I want to come back to ‘What are the economic phenomena going on and what are we doing?’ About the feminist side: People have various reactions and beliefs about what the word feminist means. I gave a talk one time at a university in Canada and a student wrote in the next day about the ‘man hater’ who had come to campus. When I teach my students I always ask them to start with a definition of ‘feminist’ and ask them whether a man can be a feminist, etc. So, to me, feminism is not treating women as second-class citizens, as there to help and entertain men. And then more my methodological work has been about the biases that have been built into economics by choosing only the masculine-associated parts of life and techniques and banishing the feminine-associated ones. In my own life, I’m quite comfortable in both economics and feminist camps. I find when I give talks I get interesting labels. When I talk to a group of relatively mainstream economists I’m a wild-eyed radical leftist feminist nutcase. But because I’m an economist, when I talk to a lot of gender and women’s studies groups, and I don’t talk about the evils of global corporate capitalism and I don’t have a certain line that I take on the economy, I’m considered a right-wing apologist for capitalism. And I’m quite comfortable balancing those two. I think that the people that spout a certain kind of left-wing creed about the economy actually listen too much to neoclassical economists, because neoclassical economists are what? They are the people who taught everyone that business has to be self-interested and about greed. That is not necessarily the case in the real world. But they invented it. Marx actually kind of picked it up from Adam Smith, this idea that there’s a mechanical economy with certain drives and engines. And that has sunk in so much that we’ve forgot that things like machines and drives are metaphors and that the idea of profit maximisation by firms was adopted because it fits nicely into calculus optimisation. Economists felt like physicists by adopting that.

I: This is very interesting because it leads me to a question I wanted to ask you, which is a sort of a critique to feminist economics. That in some ways, is this critical standpoint –feminist economics- simply a specific manifestation of a deeper problem within society? The Marxists occasionally take this view, that it is one manifestation of a deeper problem of subjugation and class issues. Or is it a viewpoint which should be explored in itself without going deeper into social theory; that is embedded in other structures?

R: There is a big area in feminist work that usually goes under the term ‘intersectionality’. It is about how gender interlaces with class, with caste, ethnicity, immigration status, nationality, race, and all the rest of these things. I think of the feminist analysis as a particular way in. There are a lot of people who do a lot more work on those fronts than I do. The gender aspect, along with explanations coming from economic power and class, I think, together explain a lot of the power of the mainstream in economics. That is, the mainstream is supported in part because it kind of throws a smokescreen over inequalities which we would rather not look at. For example, in the US, these ridiculous CEO salaries, some people spout a free market sort of thing to justify that. But then also I think there is a psychological dimension to the power of the mainstream. It seems to be more macho, more rigorous, somehow more scientific, and builds this big barrier of math: ‘Well, you don’t understand the policy because you can’t read this journal article’. I think this is rather silly and that the more we reveal that the emperor has no clothes, maybe, the easier it will be to knock down.

I: I really like your terminology which I’ve seen also in your work. You associate macho with mathematical and scientific.

R: Well, ‘scientific’ with quotes on it.

I: Yes, of course, and male. Why do you think there’s a link?

R: I call it ‘cognitive gender’ because I’m not at all talking about men being better at math. In fact, if you do one of these meta-analysis type things, again, you find the distributions of male and female math abilities are almost on top of each other. So, it’s not about men and women being different. But there are long-running cultural associations of certain things with masculinity and other things with femininity. And some psychologists have done empirical work on this. For example, cat and dogs. Do they have gender connotations? In most western society, people will tend to think of cats as somehow more feminine, dogs as more masculine, even though there are obviously male and female cats and dogs, and male and female cat and dog owners. But we have these associations. One of the ones I thought was funniest, I picked up in reading, was that the Pythagoreans gendered odd and even numbers. Some contemporary people don’t sense this at all, but other people see it and it tends to be the same way as thought of back then: even numbers a little more feminine, odd numbers more masculine. Pythagoreans explained that the odd numbers were more masculine because they could not be ‘penetrated by the number two.’ So all those numbers out there are getting it on! It’s that kind of level in which, if I say engineering or if I say blue versus pink or competitive versus cooperative, a lot of people will go ahead and sort those into gender categories. And that’s the sense in which gender has a lot of unconscious power about the way we think.

I: Those are very interesting examples you gave. I was wondering therefore if we can actively in our discourse and in our work eradicate the gender difference, or we should simply be aware of it, because it seems to be extremely ingrained. If it goes back to the Pythagorean school and other examples in other cultures, it may be the way we are wired to think in many ways.

R: I’ve had some people argue to me that we should just become entirely gender neutral, just not gender anything, which I think is probably not very realistic. There’s some pretty good arguments from child development that children see from an early age that some people have beards and other people don’t and just start to build this up pretty early. But what you can do is, as an individual, try to be aware of its effect on your own thinking. And then that’s really not enough because we never really get to see ourselves think so well. So I think we need to make sure that whatever kind of decision making groups you’re in, we need to have enough people of diverse backgrounds so they will be able to call each other on unconscious biases all along the line. That second step is very necessary because there’s only so much that trying to think past our own biases will get us.

I: I can see that. This brings me back in the discussion about whether mainstream economics has done this reflective exercise to a large degree; has it been, at least, reflective on the biases it has. You gave us an answer before on this. Do you think your work and the creation of the feminist field has changed that a bit? From the early 1990s and early 2000s I mean.

R: My work changed the field?

I: I mean the development of the field of feminist economics has created the reflective attitude in the profession?

R: I don’t believe so. The attitude of the mainstream, and even people that are a little bit around the edges of the mainstream, people like, say, Paul Krugman or Joe Stiglitz, who take the mainstream to task on certain things, have not really gotten the gender angle at all. And then the bulk of economists I think are quite unreflective about the source of their models and methodology. It just seems to them naturally obvious that this is the rigorous way to go about it and anybody who doesn’t believe them is not up to snuff.

I: Yes, I see that. And some of it – you mention it in your work – is the way economists are trained from their undergraduate all the way to their graduate school. So, I wanted to ask you what are your ideas about the current state of the economics curriculum and how do you see it changing?

R: The curriculum is something that I’ve done some work on myself, just at the introductory university level and with a little bit of an intervention into high school teaching. Because even people who say some rather sensible things-- I’m thinking here of Paul Krugman again--if you look at his textbook, or at least the early editions of the textbook that I looked at, they were not that much different from the more standard mainstream ones. The textbooks I worked on with Neva Goodwin and others, called

‘Principles of Economics in Context’ and

Micro- and Macroeconomics in Context, shifted the introductory curriculum a bit more, but not to the point where it would become not the thing that people expect introductory economics to teach. That is, we kept teaching some of the same things, such as supply and demand models, consumer/producer models, and that sort of thing. But we made some big switches. One is we taught them as

models. We taught them as ways people

have thought up of trying to think about markets or trying to think about firms or consumers, and then went on to present other things. So for example in the chapter on consumption, we also talked about the rise of consumer credit, kinds of consumerist attitudes, effects of consumption on ecological matters- after introducing the mainstream or neoclassical economist schools, because there’s this way and then there are these other big economic issues having to do with it. We also introduced things like public goods and externalities in chapter one. We discuss income inequality I think around chapter three or four. A lot of books do it but it’s in like chapter eighteen that you never get to. Most economics textbooks say that your three main economic activities are production, distribution and consumption. We added one on the beginning, that we called ‘resource maintenance’, which sounds quite neutral. But the standard economic approach never tells you where natural resources or workers come from--they just kind of pop up--or where waste products and sick people and old people go--they just kind of ‘poof’, disappear. Well, these are really the subjects of ecological economics, and of feminist economics to the extent that it looks at women’s traditional work in raising children and taking care of the sick and elderly. So, by bringing in resource maintenance we can bring in a whole lot of things about sustainability and gender from the beginning.

I: Do you think by bringing in resource maintenance as a topic you are questioning one of the standard definitions in introductory economics that economics is about scarcity or is it reinforcing that message about scarcity and choice?

R: Well, the definition of economics that we use in the books is sometimes called a ‘provisioning’ definition. That is, ‘economics is about how societies organise themselves to provide for the survival and flourishing of life’--or sometimes at the end I put, ‘or fail to do so’. Some economies fail to do that. The tendency within economics to define it as choice in the face of scarcity or as markets is too narrow. Studying provisioning is really what the person on the street expects economists to be doing.

I: And it has to do with individual choice.

R: Yes, in the standard definitions.

I: In the standard definitions. The interest in provisioning in your definition comes close to some of the work of, I think, economic anthropologists, who speak about the relation of society and economic life.

R: Yes.

I: I wanted to ask about your work in the family and the gender roles within the family in economics. Can you tell us a bit about that?

R: I haven’t worked in that a great deal. I worked on some issues of household consumption and equivalence scales. I worked on issues of household taxation. That is there are some tax systems that have a disincentive for a second worker and that could be made more fair. What I’ve been doing more recently, actually, is critiquing the traditional economic roles of the man in the family and in the economy. I’m giving a talk later today on the topic of ‘financialised masculinity.’ That is, the woman in the traditional Victorian image of a family, she is the nurturer, the carer, the altruist, the person that takes care of the family. What’s the man’s role? Maybe disciplinarian, but mainly breadwinner. The man is about the dollar signs. The woman runs the family, he contributes the money to it. And that’s a very narrow idea of what men are as well. There is an idea that a chief executive officer has to be incentivised by money to run a company in a certain way. Well, other people get paid and are just expected to fulfil their responsibilities. Why can’t a CEO be expected to fulfil some responsibilities? That’s a broader image of what a person is than ‘you have to incentivise me at every step to do something.’ So, I went away from your question there but I think there are interesting things to look at about in terms of the model of the traditional male role in the family.

I: Let me return to teaching, if I may. You mentioned about the problems of teaching. Do you think it’s a question of content in what economists teach or is it the way of delivery or is it a bit of both?

R: I think it’s a bit of both. I think there’s a fair amount of work in mainstream economics about the delivery part. Some gets into

The Journal of Economic Education. I see the bigger problem as being the content problem and I think the content drives some really good students away. If students want to be doing work relevant to real world problems they may rightly see a whole lot there that may not be helpful.

I: So, you mentioned how to bring the feminist perspective in at the research level and you’ve given us a lot of examples. Could you give us a specific example of how you bring this into the classroom and how you make students in the first year or in the second year of study aware of the issues?

R: There are different – it’s almost a pun – schools of thought about this. There are some people who believe you should start from the beginning, teaching about different schools of economic thought, and then you might teach about feminist things. Most of my students, I have found, are not really intellectually able to deal with that kind of high-level intellectual disagreement, right off the bat--although I am going to experiment this spring, starting a class with a little bit more of that. So, I have tended to expect that my students coming in, want to learn something about the economy and something about some ways to look at that and analyse that. So, in an introductory class, for example, on the macro side, every textbook has a line about how unpaid housework is left out of GDP. You can go further with that, you can talk about the size of this contribution, satellite accounts, other things. You can also talk about wellbeing indicators, as opposed to just GDP indicators, which gets to a much more real-world set of issues. Also, when you’re talking about labour markets you can bring in topics of discrimination, stereotyping, occupational segregation, and in studies of the household you can bring in models of the household that are not just based on a single household head.

I: You started your quote by saying ‘different schools of economic thought’ is a way to start teaching, although it is a highly abstract way to do it and it has its problems. And then you mention feminist economics, so do you think it should be presented as such? I mean, is it a school of economic thought or is it a perspective within the schools of economic thought?

R: I think it can be both. You could see me as a feminist economist. Given the training I came from, most of what I reflect on and work with was from my own relatively mainstream training. There are other feminist economists with whom I don’t share much vocabulary, or they come from a Marxist feminist background and are doing something quite different.

I: Is there something else you would like to talk about, in teaching? I was going to ask about your textbook but you’ve pre-empted me.

R: I was just talking to a group of teenagers from various European schools in Brussels last week, and there were two issues that caught them, which really seemed to have their interest. One of them was inequality. The question I asked them was ‘What do you wish economists were doing better?’ after I’d described what economists do, and one issue that came up was inequality. But the other one was climate change. The next generation are the people that are going to have to live with these decisions that are going on. And the science has become indisputable, except by people who are choosing to close their ears. But in a lot of countries the question has then moved on to ‘Well, what’s the economically optimal way to address this?’ The US tends to be far behind most of Europe on climate change. It’s gotten phrased in the US as ‘How do we address climate change without it costing too much in terms of GDP?’ So, a friend of mine, Frank Ackerman, has written a book satirically entitled ‘Can we afford the future?’ Is the future going to cost us too much? The title points out that this is kind of a silly way of looking at the problem. I don’t think economists should be making the decision about how fast to adjust. I think that needs to come from science and democratic political decision-making. I think actually there is a role for standard economic models in this, along the lines of cost-effectiveness analysis. It’s hard to quantify the benefits so I don’t think that cost-benefit analysis is a strong point here. But cost-effectiveness analysis could be useful. That is, standard economics tools could be very useful in answering ‘Well, shall we push for more wind or more solar next, to meet a target?’ That is something that some of the standard tools could work on. But the larger issues of how fast to move and how to move, I think, are very tangible to younger generations, and are topics where broader thinking about economics could be very useful.

I: Leading on from that, ecological economics is a big field. You mentioned before there is an interface with feminist economics as well, could you tell us a bit more about that? What would be the feminist perspective within these fields? Because someone critical may argue, this seems to be something where we can agree on without having to go into a feminist perspective.

R: For example, I’m actually here in Europe to participate in a conference next week on ecology and feminism. We’re doing a special issue of the journal

Feminist Economics on ecology, sustainability and care. And so there’ve been these somewhat parallel literatures developing in feminist economics and ecological economics about these things that I said are left out. You don’t know where the resources and the workers come from; you don’t know where the waste products and the sick and old people go. It’s really women’s traditional work and the natural environment that have been left out. That’s not to say that every ecological economist is feminist or that every feminist economist has an ecological concern. That’s definitely not true. But there have been sessions at conferences, special issues – this will be the second. There’s a special issue of

Ecological Economics, I think back in the late nineties, on feminism and ecology. Different perspectives can be brought in. For example, one of the papers that we’ll be discussing next week is about how time use relates to ecological and feminist issues. Some ecological economists are saying, well, one way we can move towards a more sustainable economy is reduce the length of the work week. People can enjoy more leisure, and hopefully engage in less fossil-fuel oriented consumption. But some of the proposals are for cutting the work week by a day. If you look at it from the point of view of a parent responsible for small or school-age children, that’s not going to be so helpful. That means four days a week you’re still trying to get to the day care centre before it closes and you’ve got all of that kind of stuff going on, or arranging after school care and the rest. So, when you put the two together, and bring in feminist input into the question of working hours, you might be talking about a shorter working day rather than a shorter working week when you take into consideration the way that childcare and other things tend to be scheduled.

I: So in some ways the perspective of feminism in ecological economics could really move us forward by reorienting the basic elements of how we see the economy? Is that part of your answer, do you think? If we move beyond scarcity and other definitions and move towards provisioning, that is seeing about generations which are yet to come, seeing about things which we can’t formally account of, that could be a way of creating that link?

R: Yes, I think feminist economics and ecological economics share more of a focus on this kind of provisioning definition of economics and about economics ultimately being about wellbeing, not just in the short term for us, but across countries and across time.

I: I wanted to ask you something that you wrote back in 2000 when you were asked ‘Where is feminist economics going?’ And you answered that your agenda has three parts. One, to redefine the field of economics, two, to revisit the value system underlying the discipline, and, three, to bring feminist insight into real world economic issues. And in your answers this far, you’ve outlined aspects in all of these. So, in your mind, how has your agenda changed since then? And how do you see it moving forward?

R: Since 2000.

I: Yes.

R: I would say I have gotten more concerned with the ecological issues, particularly as climate change has become increasingly obviously real. I’ve become concerned with this backlash, like I said--the stereotype-creating literature coming out of behavioural economics on so-called gender differences. I guess my attitude towards the profession has become neither more optimistic nor more pessimistic. My attitude towards the progress of the things I’m interested in the world took a big setback this last November [of 2016] in this US elections. So while it’s always been a tough time to be working on these issues, it just got a whole lot tougher to be working on feminist and ecological concerns in a US context.

I: We don’t need to go too much into current affairs, but do you think that since the financial crisis there was an opening for more critical perspectives? And then you see in the current US elections and other places these critical perspectives at the political level have been taken up by very different viewpoints.

R: I think there was a real lost opportunity at the financial crisis. And it wasn’t lost by people not trying. Mainstream economics as well as the more mainstream parts of Republican and Democratic parties in the US all wanted to bury it and not really fess up, not really reregulate, not really do anything about it, not really change the sorts of analysis. The economics profession came under some heavy criticism for not having seen this thing coming, which I think was well-deserved. But that dissipated without actually causing a lot of changes. A lot of the outrage about the leaders of the investment banks and such, and the illegal foreclosures and the rest didn’t really come to much in terms of our reregulation or policy solutions. So, I think that in relation to the last election there was a lot of distress related to people losing their houses in the financial crisis, and distress related to trade pacts that were entered into with some idea that there would be some adjustment of systems for workers, but that never really materialised. There’s a lot of pain being felt by many that got taken advantage of.

I: Why do you think that has not moved us forward to an agenda which is not right-wing?

R: In the US you saw Bernie Sanders getting early support from some segments and then Donald Trump getting support from others. It very quickly became clear this wasn’t just going to be left versus right, it was going to be insider versus outsider. I think the right is a lot more savvy about reaching and motivating people through various kinds of media. Trump got himself on the front page every day. That’s what he’s savvy about—using the media. There’s also been some very interesting work written by people like George Lakoff, Arlie Hochschild, and Jonathan Greene, about what motivates people and what gives people their ethical and moral compass. The Republicans have for several elections been better at pushing more buttons and getting out the good slogans. A lot of us, particularly people who consider ourselves on the progressive end of the political spectrum, but especially academics, expect that we can convince people by reason. Oops! It’s not that I want to give up on reason, but one needs also to be more sophisticated, again, from this behavioural, psychological perspective, about ‘what do people understand?’ When are they willing to actually even hear anything? How does it fit with their self-perception and the way they think the world works? We’ve been very naïve about that, thinking that a lot of people in the world think like us, which is not the case.

I: Do you think the 2016 US elections show that a broad part of the population would, perhaps, have an interest in any type of feminist perspective? Because, in some ways, the two candidates were divided in many fields, but they were also divided on the role of women, or at least how they articulated that in the public debate.

R: What’s going on with right-wing women I think is very complicated and I find it appalling that anyone with a daughter would vote for Trump, a person who has bragged about sexual assault. But life is more complex than that and there are a lot of people who would never call themselves a feminist yet believe people should get equal pay for equal work. They may not support abortion, but they’d certainly be inconvenienced if contraception was banned again. They believe that people should not be beaten by their spouses. There’s a lot of things that were won by earlier feminist waves that they would not want to give up even thought they might say ‘Feminist: I don’t want that word, I don’t want to be identified that way.’

I: I’m wondering, on a more personal level, because this is reflecting that I do when I see these election results and they are unexpected by me, whether you’ve had a situation as a researcher that you started to investigate something and that research has completely changed your understanding of what you were doing? Do you have a situation where you’ve completely changed your mind by dealing with a real world issue?

R: I think some of my initial exposure as an undergraduate to some basic statistics about what was happening with men and women in the labour market was very important for my formation as a feminist. I certainly had not been up until that point. I’ve had my eyes opened to a few things. I was really curious, like when I started doing this research on gender and risk-aversion, ‘Is there empirical evidence for this out there?’ I’m enough of a social scientist to say ‘Well, maybe I was wrong.’ It turns out I wasn’t wrong, but the issue had gotten so polarised into either men and women are categorically different or absolutely identical that people had forgotten there’s this whole span in between for ‘largely similar, tiny bit different.’ I’ve been called on the carpet sometimes for forgetting to properly nuance what I’m saying, because often I’m talking about gender stereotypes as they exist in dominant white Anglo-European culture. So, for example, the association of women with weakness and men with strength is not necessarily true if you go into other cultural categories. Historically, black women in the US were not thought of as being weak. So, I do have to remember to clarify what context I’m particularly talking about. I guess that is something that has become more clear over time.

I: My final question has two parts. If you had an undergraduate student, starting their undergraduate education now in economics, what would be your advice to them? And if you had a graduate student starting their research in economics, what would be your advice to them?

R: I guess the main thing is, if you’re really interested in making a positive difference in the world and you think economics might be a good way to do it, please stay in and work on it and help us turn this into something useful. The undergraduate student, I would also pragmatically advise depending on where their interests are, and where their strengths are in terms of math and verbal analysis. If they were weak on math I’d probably say ‘Well, maybe you want to do a public policy track with an economic focus rather than economics graduate school’ because, right now, the first couple of years of economics graduate school tend to be pure math. I’m not going to send lambs to the slaughter by misadvising them that way. Someone in graduate school in economics, I would assume they had probably figured this out and, again, I would encourage them to persevere if they want to make some good in the world, are willing to do it. Seek outside support. It is possible to become so socialised, so much so, that you forget why you’re there and lose that critical edge. So, often doing some outside reading, keeping some outside support group or, even better, an inside support group while you’re in graduate school is a very good idea. If they want to study because they think the math is really clever, I’ll give them some pragmatic advice but I don’t think what they would be doing would be very interesting.

I: Professor Nelson, thank you very much for your time and for the discussion.

R: Great, thank you.

(End of recording)